Most raw materials for printed circuit boards (PCBs) are still produced by conventional methods. Recently, manufacturers have begun exploring new techniques. These methods aim to lower costs, improve material performance, or both. The processes used to make copper-clad laminates and prepreg (also called bonding sheets or semi-cured sheets) for multilayer PCBs are generally similar.

Traditional Manufacturing Processes

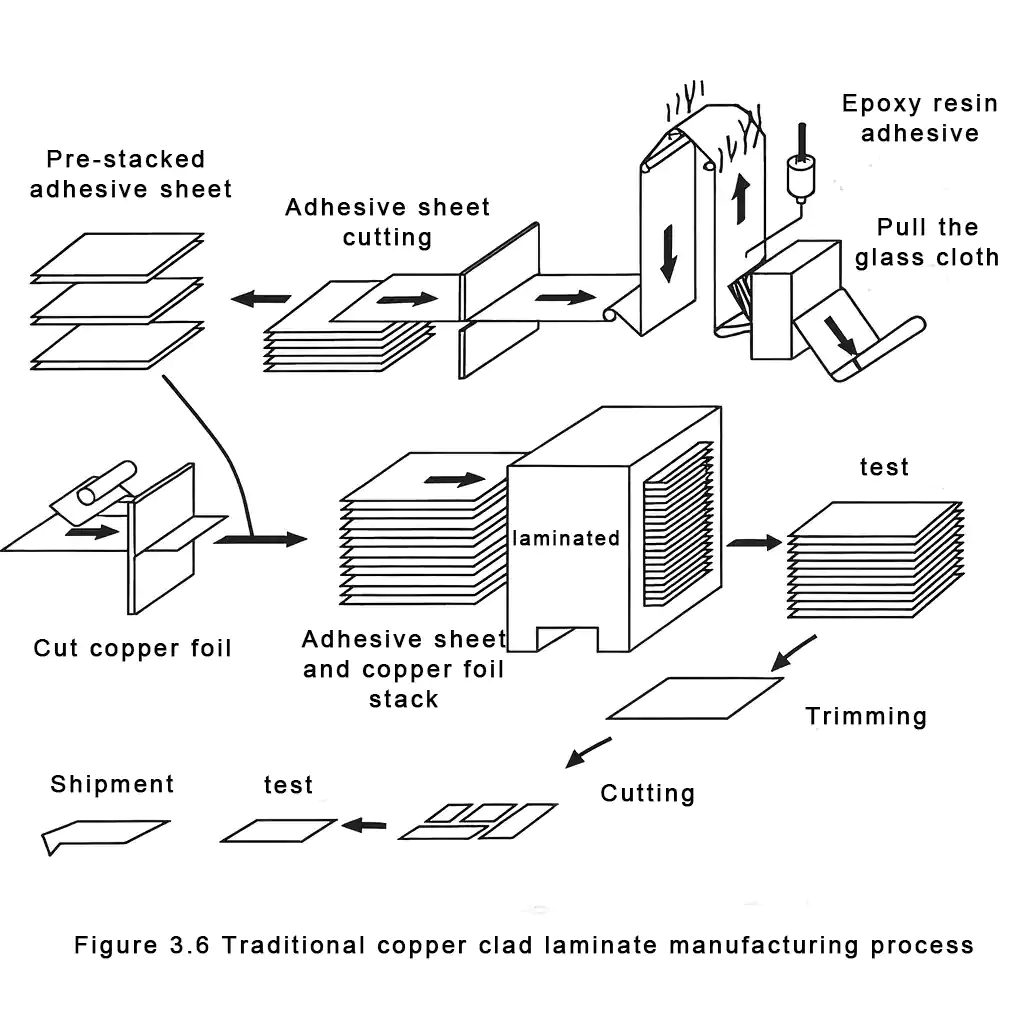

Figure 3.6 shows the overall traditional manufacturing flow. This flow can be divided into two parts: prepreg production and laminate production. Prepreg is also known as “B-stage,” while the laminate is sometimes called “C-stage.” These terms describe the degree of polymerisation or cure of the resin system.

B-stage: a partially cured state. Under elevated temperature, the B-stage resin softens/melts and continues to polymerise.

C-stage: a “fully” cured state. (In practice, 100% complete cure rarely occurs; “fully cured” means that the vast majority of reactive groups have crosslinked so the resin will not continue curing even at higher temperatures.)

Prepreg (adhesive sheet) Manufacturing

In most processes, the first step is to apply resin to the chosen reinforcement—most commonly woven glass fabric. Rolls of glass cloth (or other reinforcements) are run through a coating line, commonly called a treater or an impregnation line.

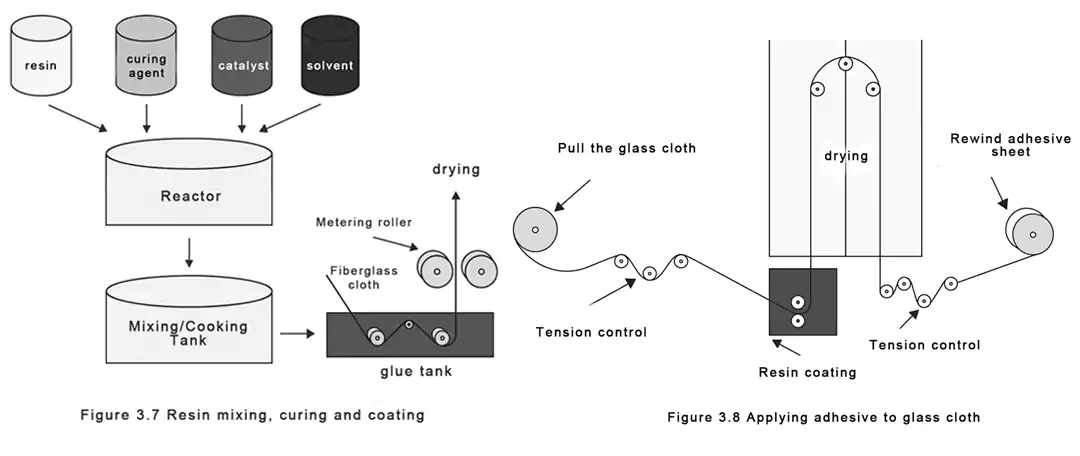

As shown in Figure 3.7, the resin and other formulation ingredients are mixed and matured in a reactor before coating. In the treating process (Figure 3.8), the glass cloth passes through a resin bath, and precision metering rolls control the post-coat thickness to ensure the resin fully penetrates the gaps between glass bundles (see Figure 3.9).

Next, the resin-coated glass cloth passes through a series of heated zones for drying. These zones typically use high-velocity forced-air convection, infrared heating, or a combination of the two. In the first temperature zone, solvents in the resin formulation evaporate. Subsequent zones partially cure the resin, bringing it to the B-stage. Finally, the finished prepreg is rewound into rolls or cut into sheets.

Key process controls include:

- Resin formulation: Control component concentrations to keep resin viscosity within the acceptable processing window.

- Web handling: Maintain stable tension through the line; prevent twisting or distortion of glass bundles.

- Critical attributes: Control resin-to-glass ratio (resin content), degree of cure (gel time), and cleanliness/foreign-matter control of the prepreg.

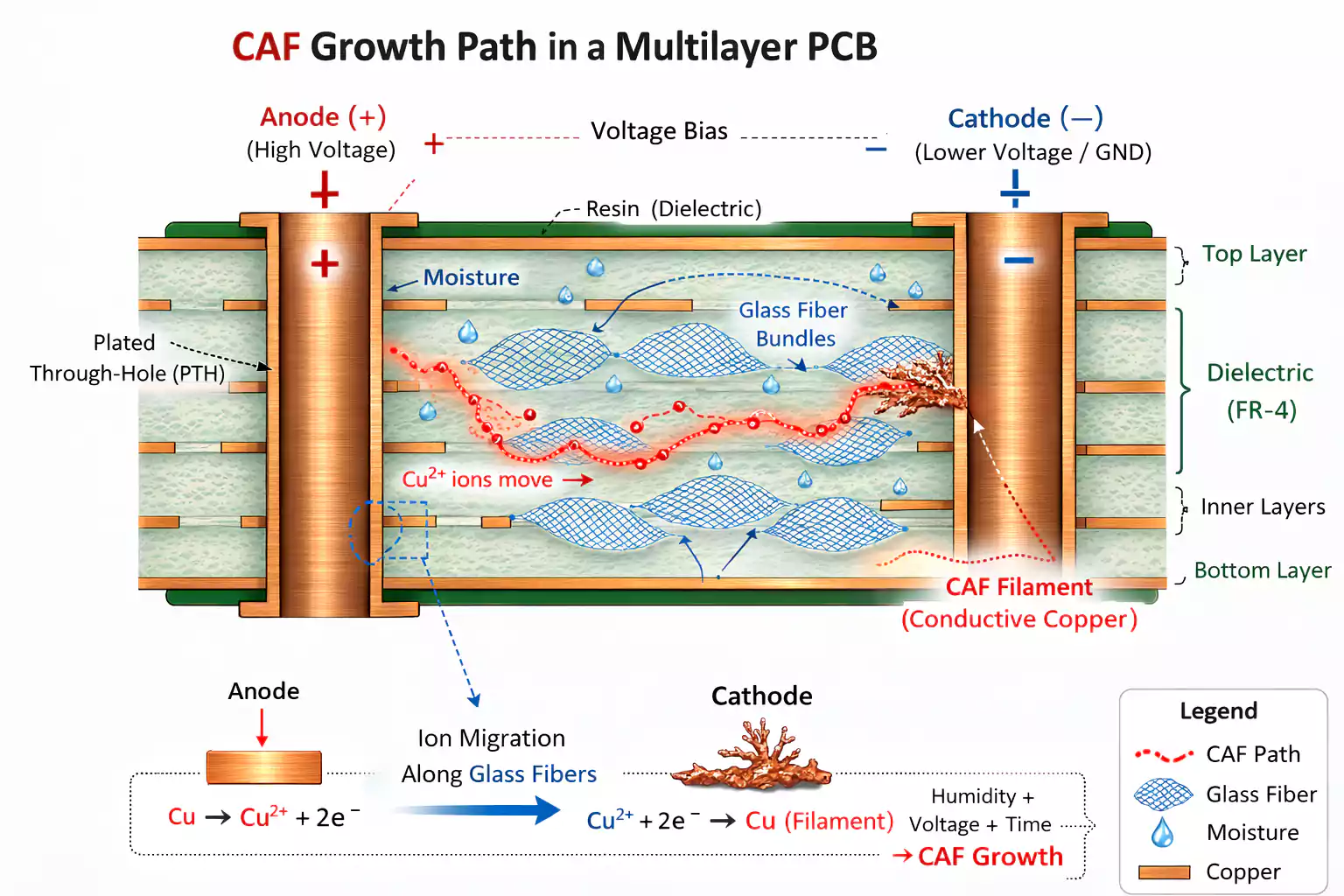

Because the resin is only partially cured, storage temperature and humidity must be tightly controlled. Temperature affects further curing. This influences the performance of subsequent laminates or multilayer boards. Moisture interferes with curing agents and accelerators. This disrupts lamination. Absorbed moisture can also cause voids or delamination in the laminate or finished multilayer PCB.

Laminate Manufacturing

Manufacturing copper-clad laminate starts with prepreg. Prepregs with different glass styles and resin contents are combined with copper foil of specified grades to form laminates. First, the prepreg and copper foil are cut to size (Figure 3.10 shows an automatic copper-foil shearing process).

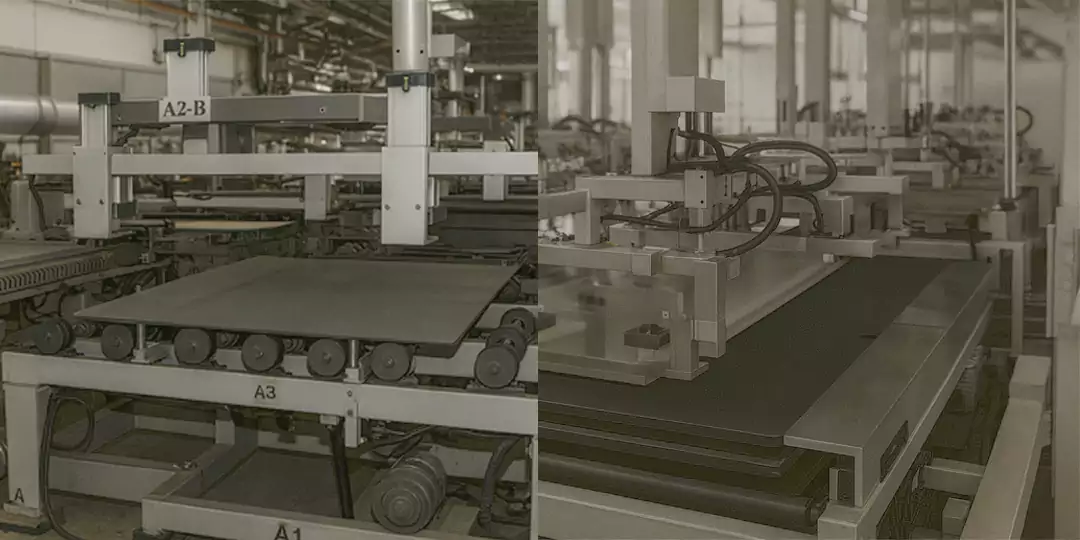

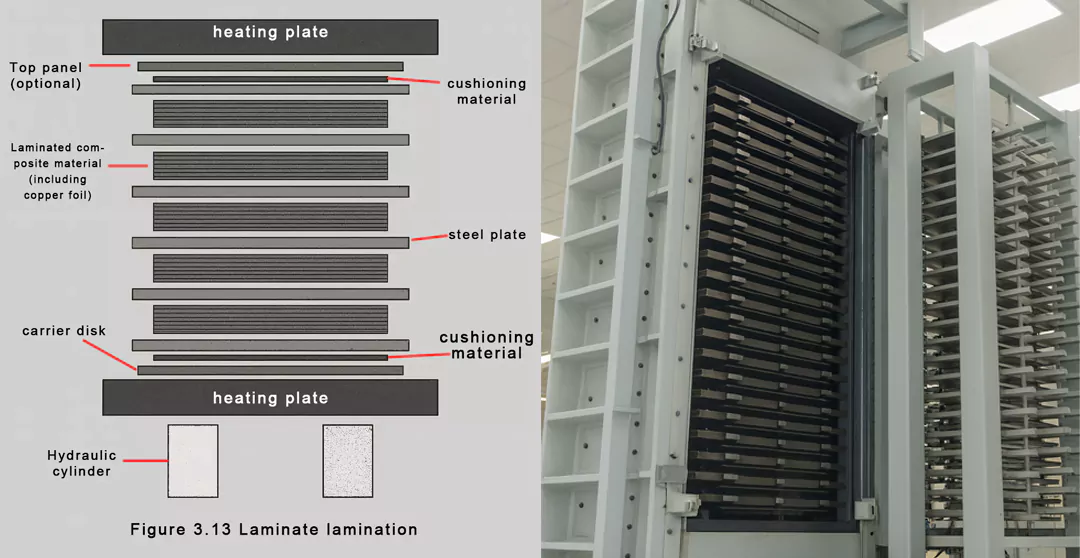

Next, the materials are stacked in the proper sequence to build the desired laminate. As shown in Figures 3.11 and 3.12, automated processes pre-assemble prepreg and copper foil before lamination. These pre-assembled “sandwiches” are then stacked together, separated by materials such as stainless-steel plates, aluminium, or others. Once stacked, the assemblies are loaded into a multi-opening lamination press (see Figures 3.13 and 3.14), where pressure, heat, and vacuum are applied. Because resin systems, B-stage level, and other factors vary, press parameters and cycles differ by material.

The press contains multiple hot plates heated by steam, thermal oil, or electric heaters.

Critical lamination controls include:

- Cleanliness: To achieve good appearance and avoid embedded debris, maintain cleanrooms and clean separator plates.

- Thermal/pressure profile: Control heat-up rate and pressure so the resin flows properly and wets out the glass; control cool-down rate to minimize bow and twist.

- Cure above Tg/peak temperature dwell: Time above the resin’s cure temperature determines the ultimate degree of cure.

Although the description above is brief, many interrelated factors affect the final laminate’s quality and performance. Changing one variable can influence others, so process adjustments often require coordinated changes elsewhere. In short, prepreg and laminate manufacturing are more complex than they appear at first.

Direct-Current (DC) or Continuous Foil Heating Lamination

Continuous metal-foil or DC heating processes offer an alternative method for producing copper-clad laminates (see Figure 3.15) and can also be used for thin PCB substrates. This approach still uses prepreg, but the pre-assembly and pressing steps differ.

In this method, copper foil is used in roll form rather than sheets. One side of the foil contacts the prepreg, while the other side remains rolled. After the prepreg is laid up, the copper foil is placed on the opposite side to form a laminate panel. Two copper rolls, possibly of different grades, can bond to both sides of a panel simultaneously with anodised aluminium plates between them. These stacks are then pressed under heat, pressure, and vacuum. Unlike standard lamination, DC passes through the copper to precisely control heating.

Continuous Lamination Processes

Continuous lamination processes have been developed over many years. Traditional batch lamination uses sheet-form prepreg and copper foil that are pre-stacked and pressed into discrete panels. In contrast, continuous lamination feeds rolled prepreg (or glass cloth) and rolled copper foil through a horizontal laminator.

There are two variants:

- Start from rolled prepreg: Unwind B-stage prepreg and copper foil, combine into a continuous sandwich, and feed into the laminator.

- Start from raw glass cloth: Unwind untreated glass cloth, impregnate it in line, then combine with continuously unwound copper foil to form a sandwich that feeds directly into the laminator.

After lamination, the continuous laminate can be cut into sheets. Thin laminates can be rewound as copper-clad rolls. The limitation of continuous processes is that they are best suited to high-volume, low-mix production; frequent product changeovers for small lots are complex and less efficient.

Conclusion

Making laminates and prepregs is key to reliable PCB production. Carefully controlling resin, soaking glass cloth, and managing lamination produces consistent electrical, mechanical, and thermal results, delivering quality copper-clad laminates for modern electronics.